Microsoft SDL Version 5 Released

Filed under: Development, Security

The latest update to Microsoft’s Security Development Lifecycle (SDL) was released on March 31, 2010. You can download the Microsoft SDL V. 5 from here. This version has many updates around agile SDL practices. Building a secure SDLC is a priority concern for many development organizations today. Microsoft has done a great job of putting together this guidance. I recommend anyone involved in application development to take a little time to read this over.

ASP.Net Custom Headers

Filed under: Development, Security

Have you ever taken the time to look at the headers that are returned from your ASP.Net application? If you have, you may have noticed the following two headers that are added for ASP.Net:

X-Powered-By: ASP.Net

X-AspNet-Version: x.x.xxxx (the version of .Net used for the application)

Many people ask how to remove these two headers from the Response. There are different methods, depending on the version of Internet Information Server (IIS) you are using. I will address these headers individually due to how they are handled.

X-Powered-By

In IIS 6 and earlier, this can only be done through the IIS console. To do this, follow these steps:

Open the IIS Management Console

Open up the web site properties

Click the HTTP Headers tab

Under Custom HTTP Headers click on the header you want to remove, then click the “Remove” button.

In IIS 7 it is possible to remove this header through the web.config file for the application. In the configuration section, add the following elements:

<system.webServer>

<httpProtocol>

<customHeaders>

<remove name=”X-Powered-By” />

</customeHeaders>

</httpProtocol>

</system.WebServer>

X-AspNet-Version

This tag can be removed from the web.config file by using the using the <httpRuntime> tag as seen below:

<httpRuntime enableVersionHeader=”false” />

So Why Remove Them?

There are two good reasons for removing these headers. Both reasons are both debatable depending on who you talk to. First, removing these headers can help provide a little added security benefit. I know, I know, a good attacker’s toolkit will do packet inspection to determine this information. Even better yet, most asp.net sites give it away by the file extension. I am not going to argue that fact at all. I would disagree that it creates a false sense of security, that is just an excuse not to do something. The Version information is more important for the security argument. There are differences in the frameworks that make knowing the exact version of asp.net attractive. It is better to just not give it away and let the attacker try to figure it out.

Second, There is a performance gain regarding the amount of data that is transferred to the client. Again, I will not disagree that the 50 or so bytes is a small amount of data. But when you are running an enterprise application with millions of hits a day, that small amount really adds up in bandwidth.

These headers may be important while debugging with Visual Studio, but they are not important or needed for a production system. I am actually astounded by the fight to not remove these headers when it is an hour job at most (if you have to update a web farm with IIS settings). Every application is different and this is just my opinion on these headers. If you want to remove them, this should show you how.

Security Abstraction: How much is too much?

Filed under: Development, Security

I was having a conversation the other morning with a colleague and we were discussing how much security an enterprise web application developer should be exposed to. This topic has come up in numerous conversations over the past year or so and it is still debatable. The question is how much abstraction should, or better yet can, be provided to developers? A few dev managers believe that security should be completely encapsulated and their developers should not have to waste their time with it.

The Microsoft .Net platform builds in a lot of security features. Each release adds more features that help developers create more secure applications. There are a few issues with expecting these features to fully protect your application with no extra thought. First, the built in features work best when best practices are followed. For example, using parameterized queries or server controls. Second, it is impossible for a framework to account for all ways a program can be written.

Even with security built-in, does that mean that developer’s don’t need to understand what these features are? Take the validateRequest feature for example. I have asked many developers what this feature does and very few were able to explain it. So why did I pick ValidateRequest as an example? First, not many developers seem to understand it, but more important is that they turn it off. In rapid application development practices it is common to not get rock solid requirements defining the inputs for every field. This may lead to poor input validation on the server and open the application up to Cross Site Scripting attacks. I can confirm that leaving validateRequest on does not provide 100% protection from cross site scripting, but it does provide an extra layer of security. Input validation is still required, but there is a small safety net to help out.

Cross site scripting is mostly focused on output encoding and the .Net framework is getting better at automatically encoding outputs for the server controls. This solution is not whole though. If input is not sanitized correctly then some controls may allow XSS to be set in them to be sent to the browser. What if the developer decides not to use server controls and instead uses Response.Write to send some content. It is common to see sections of the application built up with StringBuilder’s and then just flushed to the client. In this type of situation, it is difficult to build an efficient framework to handle security. I guess one would have to override the Response.Write method and have it parse all data looking for HTML attributes to encode and HTML text to encode to make the data safe. At this point, it does not seem that practical.

Developers have to understand security at a base line level due to the complex nature of programming. It is not ideal to believe that security can be built into all functionality and no thought goes into it. I think it is great that frameworks like the .Net framework build some security protection in, but the developer must be able to fill the coverage gap. It is determining that gap that is more important than trying to abstract security completely.

Simplified SDL

Filed under: Development, Security

Last week Microsoft provided a document outlining a ‘Simplified Implementation of the Microsoft SDL’. This document provides the required information for minimum SDL compliance. At 17 pages, it is a quick, yet detailed, read. The Secure Development Lifecycle is not just for Microsoft projects, and can be used with any language. Microsoft has even updated the original document to include Agile development. Whether you are new to the SDL or have some experience with it, this document provides a good base of information. The document can be downloaded from the Microsoft Download Center.

Securing If Statements

Filed under: Development, Security

While recently reviewing the details of the GSSP-.NET certification, I came across the topic of “securely formed if and while statements.†At first, I was a little confused about what this really meant. I believe that a securely formed ‘if’ statement would be one that has the constant on the left, rather than the right. I have seen this many times in some code examples, but have never understood the reason for it. I think this was more of an issue for more seasoned programmers coming from languages that thrived well before .NET came along. Here is an example of this issue:

if ( myObject == null) // Less Secure *

if ( null == myObject) // More Secure

In the example above, they are both valid if statements. *They would become insecure when the developer forgets the double equal sign (==) and instead just uses a single equals (=) sign. This would not compare, it would assign, and that could cause a vulnerability. In the second if statement, if the developer tried to assign to a constant, an error would be thrown. If they tried to assign to a different variable, possibly no error, and the expected data could be modified.

Fortunately, .NET’s compiler will warn you if you do this. This would appear to make this topic sort of moot for a .NET security exam. This is how I felt too, until I came across this mistake in some Javascript code. Javascript doesn’t have a compiler, so it might be possible to miss this if the code is not tested completely. .Net developers spend a lot of time with Javascript, and may work with other languages, so it is important to understand these subtle differences when writing code.

HTMLAttributeEncode Framework differences

Filed under: Development, Security

I have done a few posts regarding Cross Site Scripting and how to protect against it. I came across an interesting item today comparing the output of HTMLAttributeEncode between .Net 1.1 and 2.0+. I thought it would be a good idea to dig a little deeper into how the encoding really works. The .Net 1.1 framework only encodes the quote (“) and ampersand (&) symbols when it renders them. In the .Net 2.0 framework, Microsoft decided to add the less-than (<) symbol as well.

Scripts do not appear to run when they are within the quotes so doing a simple <script>alert(“hello”)</script> doesn’t cause an alert box to appear when it is within quotes in an attribute. So why add the (<) symbol? It could be that by blocking this, it blocks the ability to start a script tag. Even if you are able to break out of the attribute, you could close the current element, but not start a new one.

Anything Missed?

What about the single quote, or apostrophe (‘). Not every item that is sent to the output goes through a server control. Many times, attributes are wrapped single quotes, rather than double quotes. The single quote can be used to break out of the attribute and perform an attack.

The issue here is that the HTTPUtility.HTMLAttributeEncode uses blacklisting to determine what characters to encode. The list was displayed in the first paragraph. I discussed this in this recent post Protecting against Cross Site Scripting.That post mentions using Microsoft’s Anti-XSS library instead of the HTTPUtility library for encoding data. You can read more about those at the previously mentioned link. I do want to take just a moment to give an example of the difference in output between the two methods. I output the following text to each method “> <script>alert(‘hello’);</script>

The Results

HTTPUtility.HTMLAttributeEncode

value="<script>alert('hello');</script>"

Anti-XSS.HTMLAttributeEncode

value="<script>alert('hello');</script>"

Results of Single Quoted Values (‘ onblur=alert(‘java’); t=’)

HTTPUtility.HTMLAttributeEncode

value='' onblur=alert('java'); t=''

Anti-XSS.HTMLAttributeEncode

value='

' onblur=alert('java'); t='’

Conclusion

A quick glance at the outputs and it is clear that the Anti-XSS library encodes much more than the built in routine. In the second set of results, we se that the HTTPUtility.HTMLAttributeEncode creates a new attribute for ‘onBlur’. This exposes a vulnerability in the application. The Anti-XSS version, however, does not create the new attribute, but encodes so the whole string is part of the Value attribute. This approach provides much more coverage and is just as easy to implement. It is important to understand the differences in the .Net Framework versions, as well as the external libraries that are provided. These subtle differences are what can give an attacker an opening to your application. Encode, but encode correctly.

Microsoft Introduces Quick Security References

Filed under: Security

Yesterday, Microsoft released two new Quick Security References (QSR’s) to help application development teams understand Security issues. These new guides are the first part of a continuing series to help multiple roles within the team understand common vulnerabilities. Not only do they provide great detail on the security issues, but they also help teams move toward SDL adoption.

The first two QSR’s focus on Cross Site Scripting and SQL Injection. I think it is good that they started with these two vulnerabilities because they are the two most common types of attacks. These two vulnerabilities take turns in the first and second position on the OWASP Top 10. I encourage anyone and everyone involved with applications, from the business personnel to the technical teams, to read over these guides. They are about 20 pages in length, but provide a really good description of the attacks.

The QSR’s can be downloaded from Microsoft here: http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyID=79042476-951f-48d0-8ebb-89f26cf8979d&displayLang=en

Creating the Reply With Meeting OL2007 Add-In (Part 1)

Filed under: Development

Note: This is the first part, in a multi-part series to create this add-in. I chose to break this up into multiple parts so some parts (like this one) could be used by anyone creating an add-in. This post will only create the add-in shell and will not show how to reply with a meeting. that piece will come in Part 2.

I have spent many years working with Microsoft Outlook add-ins and want to share some of my experience with other developers. Since Microsoft Outlook 2000, an API has been available for Office and all of its components. I have mostly focused on Microsoft Outlook over the years, so this post will demonstrate how to create a Microsoft Outlook add-in. More specifically, I will focus on Microsoft Outlook 2007 and use Visual Studio 2008 with C# to create the add-in. This post will show the initial creation of the project and the beginning of the add-in. I will have other posts to enhance the add-in. I chose this feature because it is included in Microsoft Outlook 2010.

Creating the Solution

The first step to creating the add-in is to open Visual Studio 2008 and select a new Project (Figure 1). The add-in will be named “ReplyWithMeetingAddInâ€.

Figure 1 (click to enlarge)

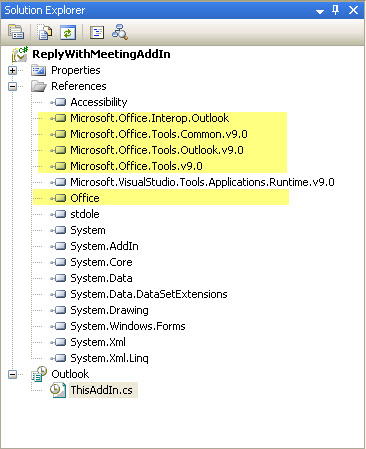

Once the project is created, there are a few items to notice. First, Visual Studio has already added the needed references to create the add-in. Figure 2 shows these references highlighted. The second file to notice is the main add-in file that was created, ThisAddIn.cs. This is the gateway to your add-in from Outlook.

Figure 2

Building the Add-in

At this point, we can build the add-in. Doing this will automatically install it into your Outlook 2007 application, although at this point the add-in doesn’t do anything. It is good to see that the add-in is present though. Here are the steps to verify that it installed into Outlook:

- Build the project from within Visual Studio by Right-clicking the project and selecting Build.

- Once the build has succeeded, restart Outlook (this is important!).

- In Outlook, click the Tools…Trust Center menu option.

- Select the Add-ins tab in the Trust Center (Figure 3).

- You should see your add-in listed in the Active Application Add-ins

Figure 3 (click to enlarge)

Writing the Add-in

The guts of the add-in start in the ThisAddIn.cs file, as mentioned above. This file initially has 2 events exposed (see Code 1).

- public partial class ThisAddIn

- Â Â Â Â {

- Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â private void ThisAddIn_Startup(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

- Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â {

- Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â }

- Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â private void ThisAddIn_Shutdown(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

- Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â {

- Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â }

ThisAddIn_Startup is used to initialize your add-in. Here you can create buttons for your add-in or link to other events within Outlook. An example would be to put System.Windows.Forms.MessageBox.Show(“Helloâ€); in this method. When outlook starts up, it will show a messagebox with your message.

ThisAddIn_Shutdown is used to clean up any resources you have used. Maybe you need to remove the buttons you created, or close down a data connection.

In Part 2 of this series, I will show the code to make the add-in useful. The add-in will be enhanced to add a button to the Main Outlook window and an email message window.

Debugging the Add-in

One of the great things about developing add-ins with Visual Studio 2008 is that debugging is easy to set up. The key to debugging the add-in is to setting Outlook as the startup action for the project. To do this, follow these steps:

- Double-click the properties for the project.

- Select the Debug tab.

- In the Start Action section, select the Start external program radio button.

- Browse to the Outlook.exe file (usually located at: C:\Program Files\Microsoft Office\Office12\OUTLOOK.EXE)

Now, when you run the add-in from within Visual Studio, it will start Outlook automatically. This will attack the debugger and you can set breakpoints just like any other application.

Wrap Up

This post shows the basic steps to create a Microsoft Outlook 2007 add-in with Visual Studio 2008. At this point, the add-in doesn’t do anything, but this is the same process every add-in starts with. In the next post, I will add the code to load the buttons into outlook so the user can reply to a message with a meeting request.

Disclaimer: This code is provided as-is. There is no guarantee to the accuracy of this information. Use this information at your own risk.

Protecting against Cross Site Scripting

Filed under: Security

One of the most important defenses against cross site scripting is encoding the output. The .Net framework provides built in routines for you. These methods, HTMLEncode and HTMLAttributeEncode, can be found in the HTTPUtility class. It is very easy to implement these methods and they should be used on all output that is un-trusted (ie, from the database, or user input).

It is simple to implement these methods. When you are sending output to the browser, wrap the output in one of these method calls. Here are a few examples:

- lblText.Text = HttpUtility.HtmlEncode(Request.Form[“fName”]);

- StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

- sb.Append(“<img src=\”someimage.jpg\” alt=\””);

- sb.Append(HttpUtility.HtmlAttributeEncode(myVariable));

- sb.Append(“\” />”);

- Response.Write(sb.ToString());

In the first line, the HTMLEncode method is used to encode a value from the QueryString before it goes to the client. it is important to note that some server controls will automatically encode their output. For example, A textbox will encode its output by default. A label control, however, will not.

The rest of the code snippet shows encoding an HTML attribute value. This is often overlooked by developers, not realizing how this can be an attack vector. It is possible for malicious data to escape out of the attribute tag and start creating its own tags or events. I have an example of this on my post about IE8 XSS Protection.

One might wonder why there are two separate methods, instead of just one. The reason for this is that each case requires a different set of characters to be encoded. The HTMLEncode will not encode characters like the quote or the double quote whereas the HTMLAttributeEncode will encode those values.

Microsoft has created the Anti-Cross Site Scripting Library (currently Version 3.1) which provides these same methods. The key difference between Microsoft’s implementation and the .Net built in routines is how they determine what gets encoded. The .Net framework uses a technique called black-listing to make this decision. This means that there is an internal list of all invalid characters that need to be encoded. The problem with this technique is that the list can be very large and new characters may be recognized later as needing to be encoded. Microsofts Anti-XSS library take an approach called white-listing. White-listing has an internal list of all valid characters and then encodes all of the rest. The advantage to this approach is that the list is smaller and shouldn’t need to get updated because the list of valid characters will probably not change.

You can download Microsoft’s Anti-Cross Site scripting Library from http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyId=051ee83c-5ccf-48ed-8463-02f56a6bfc09&displaylang=en.

Both of these approaches aim to reach the same goal, to encode output and protect against cross site scripting. It is important that developers start implementing one of these methods to help protect their applications from malicious activity. This technique may not completely stop cross site scripting, but it will add another layer of defense.

CAT.NET Microsoft’s Code Analysis Tool

Filed under: Security

Microsoft has introduced a new code analysis tool called CAT.NET to help analyze source code for security flaws within managed applications. This is a visual studio add-in that works directly within Visual Studio, so there is no need for separate programs. The tool will trace through all statements, methods, and assemblies referenced within the application. It is currently on Version One in CTP. Its rules look to identify the following flaws:

- Cross Site Scripting (XSS)

- SQL Injection

- Process Command Injection

- File Canonicalization

- Exception Information (a form of Information Leakage)

- LDAP Injection

- XPATH Injection

- Redirection to User Controlled Site

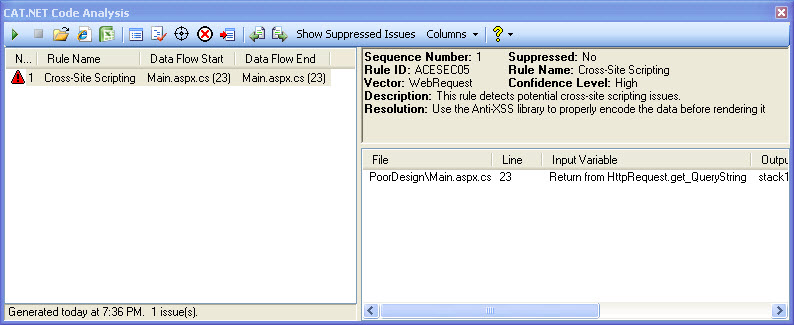

I executed the tool against a web application with the following code snippet:

The results of the scan are provided below:

As you can see from the above samples, the tool does a good job of distinguishing between threats. By default, asp:textbox will encode its text value, whereas the label control will not. The information provided by the tool is very helpful as well. It shows what file and what line of code is the offender. It also recommends a resolution to help protect against this. For developers new to focusing on security, it would be nice if the tool gave the link to the Anti-XSS library or a sample code snippet to show how to implement the fix. That information is pretty easy to find and for a free tool it provides some good general protection for your code.

The tool can be downloaded at http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyId=0178e2ef-9da8-445e-9348-c93f24cc9f9d&displaylang=en.

I have tried this tool on a few different projects and it has worked pretty well. I have found that on very large solutions I ran into out of memory exceptions. This is a limitation for all add-ins because Visual Studio is limited to 2GB of space. The larger projects use up more of that so the tool doesn’t have space to function properly. This can be managed by selecting specific projects to analyze.